#23. David v. Goliath

January 2, 2022

Corporate R&D as an investment

On a recent podcast, Steven Vannelli (founder and Chief Investment Officer of Knowledge Leaders Capital) discussed trends in research & development among public companies. And that got me thinking about how corporate R&D and the start-up ecosystem play together.

R&D is any expense that develops new products, processes, or services or improves those that already exist. Sometimes that R&D expense can pay off (e.g., better performance) or pay off massively (e.g., the iPhone). Sometimes it leads to nothing. So performing R&D is a risk because it costs money and takes time to pay off, if it ever does. But not performing R&D is also a risk. You might become Blockbuster watching Netflix eat your lunch.

Blockbuster filed for bankruptcy two years later

R&D spend is usually treated as an expense that’s written off. Maybe we’ll see the fruits in the future, maybe not. What KLC does differently is it treates those R&D expenses as a capital expense. That means they go on the balance sheet as an intangible asset. In effect, KLC treats those expenses as corporate investments that will eventually bear fruit. This allows them to identify potentially undervalued companies that invest in their future and avoid companies that are underinvesting and at risk of falling behind.

For example, in the Bloomberg R&D Leaders Index, the sum of R&D expense for the 135 companies in the index is $375 billion, while reported aggregate net income is $560 billion. If R&D was treated like capital spending, this expense would not exist, thereby boosting cash net income to $935 billion

- Steven Vannelli, Founder/CIO of Knowledge Leaders Capital

Some fun facts from Vannelli and then on to the point of this note:

Of companies in the Goldman Sachs Non-Profitable Tech Index (think recent tech IPOs: Pinterest, Teladoc, Snap, Crowdstrike, etc.), many of these unprofitable companies would be profitable on paper if R&D were capitalized as capital spending rather than an expense.

In the Morningstar Developed Market Large-Mid Index, there are 521 US-based companies. 56% of US-based companies spend $0.00 (LITERALLY ZERO CENTS) on R&D. In Asia, that number is 54% and, in Europe, it's 74%.

In all instances, the minority of companies that do spend something on R&D make up the majority of market cap. In the US, the 44% of companies that do spend on R&D represent 72% of the total market cap. In the whole index globally, the 34% who do spend on R&D make up 63% of aggregate market cap.

That R&D spend is very concentrated. In the US, the top 10 R&D spenders represent 53% of all R&D spend (the top being the usual suspects: Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Apple, Facebook, Intel, J&J). In Europe, the top 10 represent 70% of all R&D spend.

M&A City, welcome to it.

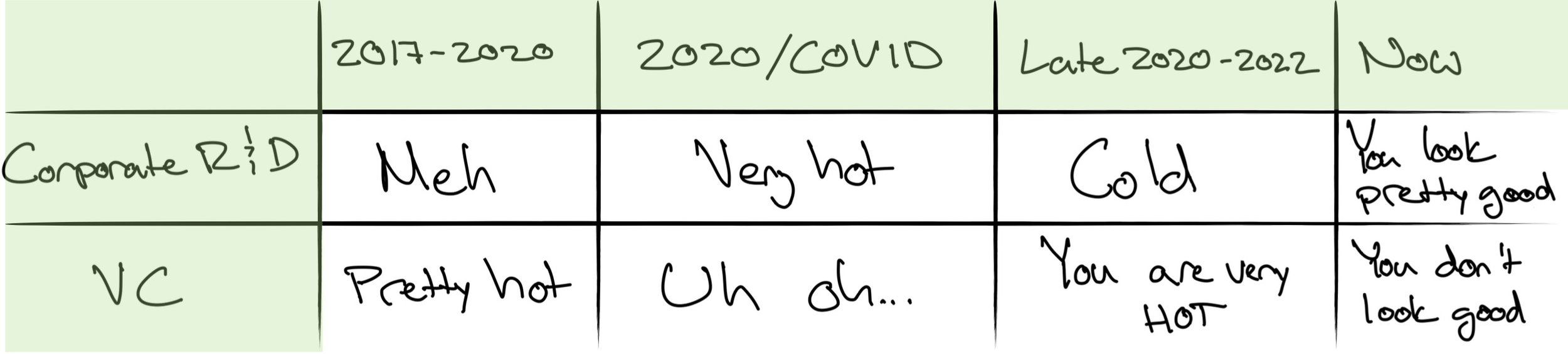

In his note Has Innovation Bottomed?, Vannelli assess the value that public markets put on R&D spend. The key metric is the difference in stock performance of the top quintile of R&D spenders v. the bottom quintile (the quintile spread). The last few years of the hottest VC market in history (2017 to now) are particularly interesting. From 2017 to 2020, the spread was relatively low (i.e., the market didn’t hugely value corporate R&D). But that spread grew significantly in early/mid-2020 (👋 COVID) before it declined for the next two years.

Source: Knowledge Leaders Capital - Has Innovation Bottomed?

Let’s look at this same time period from the VC perspective. From 2017-2020, the VC market was strong. It took a big hit in early/mid-2020 when COVID forced VCs to slow investing significantly to keep their portfolios alive. From late 2020 to this year, the VC market ripped to the highest investment levels ever.

Here’s the comparison between the two in a scientific table:

VC activity and the value the market places on corporate R&D (i.e., the quintile spread) are two sides of the same coin. So what’s happening now with the quintile spread? As Vannelli’s note suggests, it’s “bottomed” and is now ticking back up. How about VC? It’s cooling off. Funds have once again slowed the pace of investing.

The return of Bell Labs (maybe)

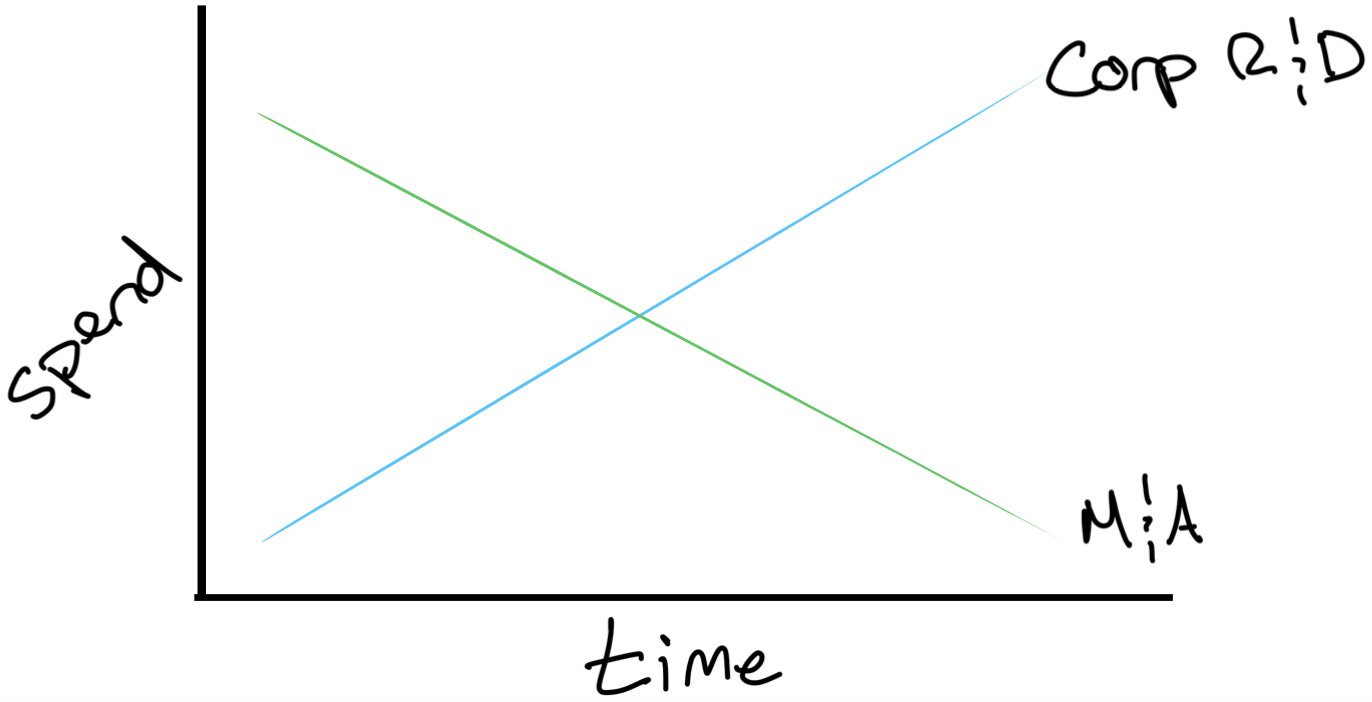

During this hot VC period, the structure of how corporates spend their money has changed. Less money has gone into R&D while more has gone into M&A. In effect, companies and industries have outsourced their R&D efforts. In this way, companies accept paying a premium when they eventually acquire the innovation (by acquiring a start-up), but they minimize the risk of failed R&D.

Unsurprisingly, pharma has operated this way for some time; acquiring companies as they pass through clinical trial phases. Interestingly, industries like CPG have done the same thing in the last decade. This high M&A activity has been a boon to start-ups and venture capital as it significantly expanded start-up exit options. In a low interest rate environment, the valuation placed on those acquisitions also grew. As valuations ballooned, corporate M&A began creeping earlier and earlier in a start-up's life. This meant that start-ups could focus on building fantastic products with fantastic demand, and then get bought early on for fantastic amounts. This has been the world start-ups and corporate M&A teams have been living until now.

But now, the heat of acquiring innovation has declined. There are two sides to the start-up environment. The supply side (money going in from investors). And the demand side (appetite from acquirers). That appetite for acquisition is why changes in corporate R&D are critical. If the public market values internal R&D spend more, organizations will spend more money on R&D, and have therefore made the decision to build innovation rather than buy it. So the exit options for start-ups from an M&A perspective are structurally changing.

More science

So what?

Founders can no longer assume they can build a hot brand/product and be the target of a high-value M&A. They have to build a self-sustaining company. It sounds obvious, but it’s a departure from the previous assumption. Companies have traditionally focused on proving out high-value products and trusting large corporates to buy an unprofitable company for the growth upside.

Founders now have to build companies for the public market: profitable, solid organizational design, internal controls, sustainable processes, etc. M&A of highly unprofitable companies will be very few and far between. In building for the public markets, start-ups will in turn be more attractive to corporates who are interested in acquiring a promising organization as a new business unit.

While the R&D spread cycles are interesting to look at in retrospect and context, they’re not a crystal ball for start-ups and VCs. The R&D spread peak/trough cycles are 1-3 years, whereas VCs invest for 5-15 years. But it does provide a good indicator. The value that public markets place on internal innovation will drive how large corporates approach it and, thus, how they will approach M&A.

For more on this from Knowledge Leaders Capital, check out Has Innovation Bottomed? and Spheres of Innovation.